LCA vs. EPD vs. PCF: An Overview

By Yangjin Yoon

Before LCA, EPD, and PCF emerged, many companies began their sustainability journey with carefully selected numbers designed to make their products look as green as possible. The natural result was a mass backlash against greenwashing and a demand for rigorous standards for sustainability reporting.

Brands, corporations, and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) responded by publicly pledging carbon neutrality targets and putting internal policies in place to meet them.

But they have a problem. 80-90% of total emissions are categorized as Scope 3 – they’re created in the supply chain, outside of their direct control. That has created a demand for transparency and product-level emission metrics.

This led to the emergence of a jumble of environmental designations; a web of governing bodies and acronyms that confuses as much as it clarifies. That’s what we’re here to help solve.

Today, three categories of reporting declarations are the leading global methods of reporting verified sustainability claims:

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A thorough “cradle-to-grave” study on comprehensive environmental impacts

Environmental Product Declaration (EPD): A document reporting the results of an LCA conducted according to specific, transparent rules called PCRs

Product Carbon Footprint (PCF): The quantified greenhouse gas emissions of a single product across a specific part of its lifecycle

So if you’re a company that needs to declare your environmental impact, which standard is right for you?

LCA: Life Cycle Assessment

What is an LCA?

A Life Cycle Assessment is a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact of a product or service throughout its entire lifecycle.

As a “cradle-to-grave” assessment, it covers everything from raw material extraction, through manufacturing, transport, use, and disposal or recycling.

It considers everything from upstream supplier data to downstream waste management. It also goes far beyond just carbon emissions, including things like water and land use and soil, air, and water pollution.

How do I create an LCA?

The four-part LCA process is codified by two international standards – ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 .

Step 1: Goal and Scope Definition

Clearly define the LCA’s purpose, product or service being assessed, functional unit of measurement, and level of detail required. In simple terms, you’re choosing the goal, use, audience, and level of review of the assessment.

Step 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

Compile the necessary data and analyze all of the relevant inputs and outputs. In the end, you should have a full list of everything that goes into and comes out of the product or service, environmentally speaking.

Step 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Classify your resource use and emissions according to their potential environmental impacts. The scope you defined in step 1 will determine how many impact categories you’ll need to use. In the end, you will have translated your inventory data into the metrics you need to complete the LCA.

Step 4: Interpretation

Turn your metrics into actionable insights. You need to determine the relative contributions and relevance of your impact sources, and review your data quality and limitations. Then, you can systematically look at ways to reduce your impact without just shifting the burden between phases of the product life cycle. Interpretation helps you use your findings to make smart decisions.

When is an LCA a good idea?

An LCA is comprehensive and somewhat flexible depending on the scope of the assessment, and it adheres to strict ISO standards for transparency and trust.

If you want to know the full cradle-to-grave scope of a product or service’s environmental impact beyond just emissions, it’s probably the best tool. The flexibility in definition also means you can expand or contract the scope according to your needs.

It’s useful for internal benchmarking, and for giving companies the trusted metrics they need to attract green capital.

When is an LCA a bad idea?

An LCA’s inherent flexibility in scope definition means it suffers as an apples-to-apples comparison. What one company may consider comprehensive, another might consider unfinished.

Most LCAs have to rely on inputs from databases (Glassdome uses ecoInvent) for some of their data – that’s completely normal. But if that secondary data becomes a large percentage of the data in your report, it can severely cut down on its accuracy.

A good LCA will also require a serious time and financial commitment. It is a complex, time-consuming, and data-intensive process that requires coordination up and down the supply chain. If you’re trying to nimbly respond to regulation or benchmark year-over-year, it might not be a great choice.

EPD: Environmental Product Declaration

What is an EPD?

An Environmental Product Declaration is a document that provides the quantified environmental data of a product based on a set of standards called Product Category Rules (PCRs).

An EPD is based on an LCA that is performed according to the criteria contained in the PCRs the company selects. Or, in less acronym-heavy terms, you assess your environmental impact according to certain rules that you choose, then write it down in a standardized document.

EPDs show the environmental performance of a product in a consistent, credible way and include a broad set of impacts, including carbon emissions, water usage, and air, soil, and water pollution.

The depth of an EPD is defined by the PCRs used. When two EPDs use the same PCRs, they provide a fair product-to-product comparison.

PCRs are based on the ISO 14025 standard and include criteria like:

- Product category description

- Goal of the included LCA

- Functional and required units

- System boundaries and cut-off criteria

- Allocation rules

- Environmental impact categories

- Product use phase information

- LCA calculation procedures

- Data quality requirements

- …and potentially even more

By so strictly defining each PCR, the standard helps ensure that EPDs are comparable to others within the same product category.

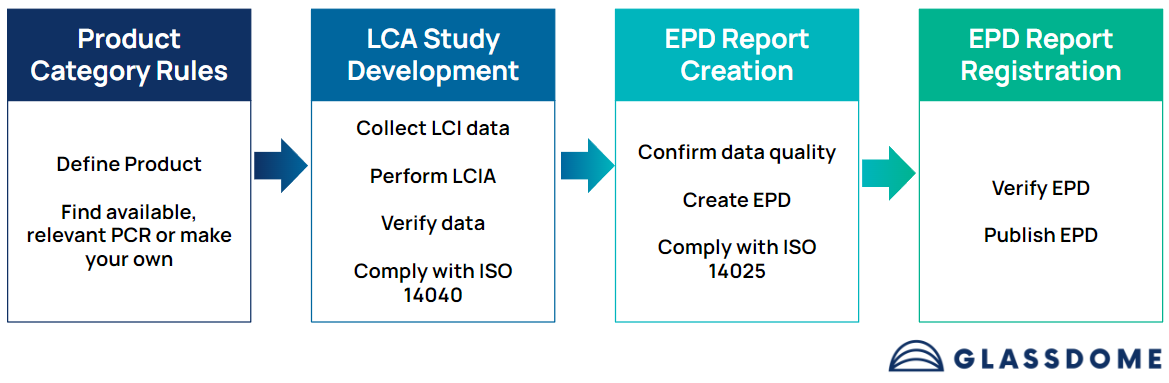

How do you create an EPD?

Creating an EPD is a four-step process, with the four-step LCA creation process nested inside it like a Russian matryoshka doll.

Step 1: Product and PCR Definition

Select and define the product you’re analyzing. Find a relevant available PCR, and, if one is not available, work with an expert to create one.

Step 2: Perform the LCA Study

See the section above. Collect your data into an LCI, perform your LCIA, interpret the results, and report following ISO 14040 guidelines.

Step 3: Write an EPD Report

Review your data quality and create your report following the ISO 14025 guidelines. Depending on your product and the PCRs you’ve chosen, other relevant standards could include ISO 14044 and ISO 21930.

Step 3: Verify and Publish Your EPD

Work with a third party to verify your EPD to ensure its credibility. Publish the EPD on a publicly accessible platform. The verification step is crucial to the EPD’s value as a comparison metric.

When is an EPD a good idea?

EPDs work very well in industries that demand transparency around cradle-to-grave environmental impact and have clear expectations about the PCRs used in the process.

Good examples include green building rating systems like LEED, public procurement policies, and specific regulations that require detailed environmental disclosures. EPDs can help companies break into and stand out in competitive markets, and support their sustainable marketing claims.

When is an EPD a bad idea?

Since they include an LCA as part of the process, EPDs suffer from similar issues. They are time-consuming to create, can rely too much on averaged-out inputs from databases, and require a large investment of time and expertise.

Industries with fragmented sustainability reporting and no clear standard for PCRs break down the ability to compare EPDs to each other, severely limiting their usefulness.

If that’s the case for you, a good idea could be to work with industry associations to develop an industry standard before committing to an EPD.

PCF: Product Carbon Footprint

What is a PCF?

A Product Carbon Footprint is the sum of the total greenhouse gas emissions created by a product, expressed in CO2 equivalents (CO2e).

Depending on the scope of the study, a PCF can be “cradle-to-gate” (how much carbon was emitted in its production) or “cradle-to-grave” (how much carbon was emitted in its entire lifecycle, including use and disposal).

How do I create a PCF?

PCF is yet another four-step process, in this case codified in ISO 14040 and ISO 14067. It is similar to the LCA process, but only focuses on carbon emissions.

Step 1: Purpose Definition

Lay out why you’re calculating your PCF. Do you want to set an internal benchmark? Are you comparing against peers? Are you doing the study to comply with a customer’s requirements (like Stellantis in the auto industry)? By defining the purpose of your study, you can ensure that the study meets your needs.

Step 2: System Boundary Definition

Determine which processes and uses fall under the scope of this study. Will it be cradle-to-grave, cradle-to-gate, or just gate-to-gate (solely the carbon emissions created inside your factory)? Correctly allocating emissions across a supply chain is crucial to delivering an accurate final PCF.

Step 3: Data Collection

Gather production process and emissions data. For a more accurate final report, use primary data. Where primary data is missing or prohibitively hard to obtain, you can also use default data from databases that contain average emissions factors and modeling information.

Step 4: PCF Calculation

Multiply your activity data by the corresponding emissions factors for each stage in the system boundary. Now you have a baseline to reduce emissions and get more sustainable.

Step 5 (optional): Third-Party Verification

Get your PCF report verified by a third-party organization. You will almost certainly need to do this if you are using your PCF for regulatory compliance, and many manufacturers require verification by their suppliers as well.

When is a PCF a good idea?

Product Carbon Footprint is the only apples-to-apples comparative metric of product-level emissions. It is transparent, robust, and simple to understand. That’s why automakers like Stellantis and BMW and regulations like the EU Battery Directive demand them.

While most other carbon footprint metrics only apply to the facility level (ie “how much carbon does my factory emit?”), PCF lets consumers see the impact of the exact product they’re buying.

The tight focus on emissions also means it is easier to replicate, monitor, and report back on once the data pipeline is set up. That’s especially true when you work with an ISO 14067-verified consulting and software solution like Glassdome.

When is a PCF a bad idea?

PCF is a powerful comparison and benchmarking tool for products. But it’s not suitable for everything.

If you are trying to look at your total environmental impact, PCF doesn’t cover it. It is strictly an emissions metric.

On the flip side, if all you are trying to do is tick a box for a less-demanding checklist sustainability, a cheaper carbon accounting software might do the trick.

How can I make my processes more sustainable?

Need to comply with government regulations, and show your customers or investors that you’re getting greener by the day? You’ll need an LCA, EPD, or PCF.

Our Product Carbon Footprint solution is the only real data solution that provides month-over-month updates on your emissions performance. Our consulting and software model, built by manufacturing experts, means you get a pipeline of primary data, and the support you need to interpret it and make improvements using our powerful Continuous Improvement tools. And our ISO 14067 certification means your report is verification-ready, cutting weeks or months out of the process.

Want to learn more?

Get in touch. After you’ve persevered through this explainer, we promise to keep the three-letter acronyms to a minimum.